Blue tablecloths: Restored tradition and regained popularity

An ancient Georgian art form is being returned to popular culture through efforts of the Tbilisi State Academy of Arts.

Traditional Georgian blue cotton tablecloths painted in various shades of blue were once a common site in Georgian households but over the years the linen has slowly been forgotten about.

Production of the ancient cloth started in the end of the 17th Century and were most common in east Georgia. At the time textile production held a special place in the country’s arts and culture industry.

In the 18th Century, artisans began creating printed textiles, using woodblocks with decorative engravings. This method was called ‘cold vat dyeing’.

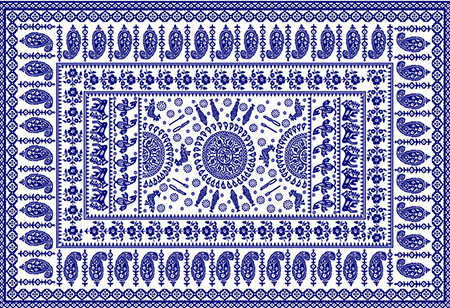

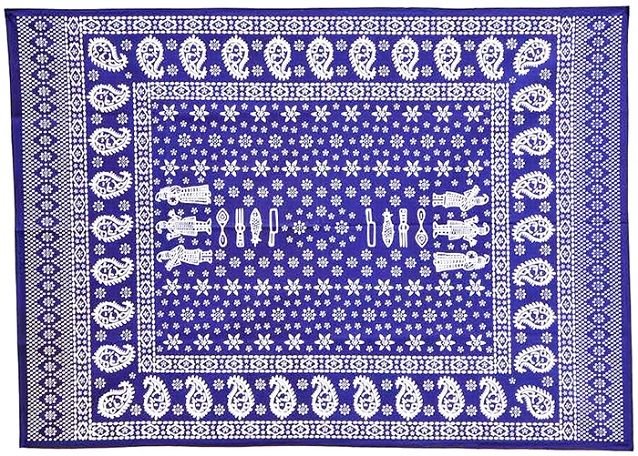

The patterns of the tablecloths often reflected the dining table; knife, fork, spoon, as well as plant and animal motifs. Photo by www.folklife.si.edu.

The blue tablecloths were produced mainly in Tbilisi, Gori and in Telavi cotton factories. The artistic motives of the blue table cloth were diverse, meaning the patterns were often different. The theme of the tablecloths reflected the Georgian people's ancient ideology using colour, texture and pattern.

Traditionally, the blue tablecloths were used in special occasions (weddings, hunting, ritual feasts, religious holidays and more) and were used by all classes of society.

On these tablecloths, the patterns and ornaments often reflected the attributes of the table: knife, fork, spoon, as well as plant and animal motifs – all symbols that were deeply connected to the ethnographic culture. The tablecloths also often portrayed dancing men and women wearing a 'chokha’ – Georgian traditional male dress.

Blue tablecloths are made of cotton and silk fabric. The traditional ornamental motifs, common compositional schemes are placed in various sizes and shapes.

Looking back on this history it is possible these tablecloths were aesthetically pleasing but also had a ritual purpose, occupying a special place in the Georgian way of life for many centuries.

As the methods improved to create the tablecloths, screen-printing techniques developed, production expanded and met increasing market demand from tourists and locals.

But by the late 1980s with the collapse of the Soviet Union, factories were closed and production stopped.

The reopening of production factories remained impossible but in in 2010 a research laboratory Lurji Supra was launched by the Tbilisi State Academy of Arts and led by the Academy’s design professors Tinatin Kldiashvili and Ketevan Kavtaradze.

The pair did many of experiments with screen-printing on other types of fabric, such as napkins, aprons and bags, and one year later they began selling textiles from the laboratory and presented them at art galleries.

Later students of the Academy successfully presented their works at the Strasbourg Christmas Market, the Artigiano in Fiera international craft fair in Milan and the Art Schools of the World – Cultural Heritage and Contemporary Art exhibition in Florence.

The laboratory’s successful ventures is helping to step-by-step restore awareness of Georgia’s ancient blue tablecloths locally and internationally so the skills of how to make the blue tablecloths are not lost but passed on to future generations.

Tweet

Tweet  Share

Share