Mtatsminda makeover: reviving Tbilisi’s iconic ridge for generations to come

The pine forests of Tbilisi’s iconic Mtatsminda Ridge are turning brown. Photo:Nino Alavidze/Agenda.ge

The pine forests of Tbilisi’s iconic Mtatsminda Ridge are turning brown. The culprits include fungi, pests, and climate change, but work is underway to revitalize the urban forest, led by the Development and Environment Foundation, under an agreement with Tbilisi City Hall and funded by the Cartu Foundation.

This four-year project will enhance the forest’s resilience, reduce natural hazards, and improve recreational infrastructure.

In the coming years, between 500,000-800,000 trees of nearly 40 different species will be planted on Mtatsminda Ridge, including diverse understory plantings to enhance the forest floor.

A mountain with a multi-layered history

Mtatsminda’s contemporary forests are the result of mid-20th century climate amelioration projects. Few trees are adapted to the mountain’s dry, exposed slopes and limited soil cover, so foresters used dynamite to create “soil pockets” to plant pine trees. Each generation in the modern era has left a mark on the mountain. In this generation, the forest will be diverse and climate-adapted.

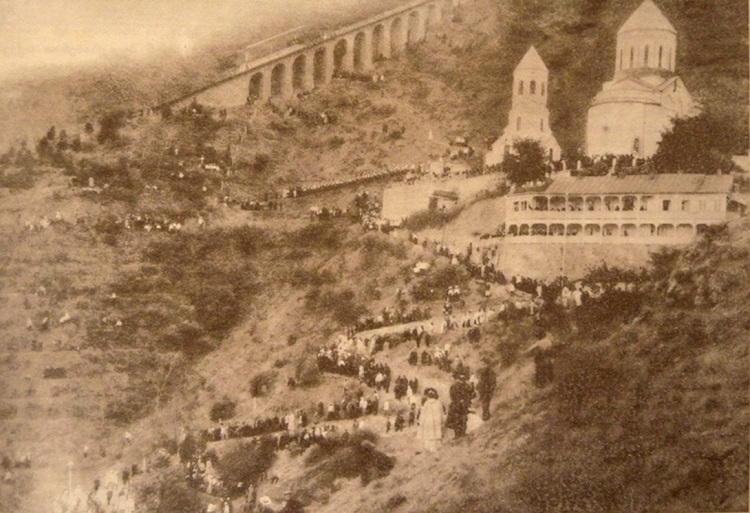

This photo from the burial of famous Georgian writer Ilia Chavchavadze from 1907 depicts the mountain’s more usual appearance. Photo: National Parliamentary of Georgia.

This photo from the burial of famous Georgian writer Ilia Chavchavadze from 1907 depicts the mountain’s more usual appearance. Photo: National Parliamentary of Georgia.

In the past, there were oak trees in the immediate vicinity of the city”, the Development and Environment Foundation’s Executive Director Gocha Koberidze told Investor.ge, “but multiple razings of the city–a step taken by many an enemy because Tbilisi forests provided shelter to guerrilla fighters–and deforestation for timber have hampered green growth.”

As Tbilisi grew in the 20th century, Soviet planners moved to ‘ameliorate’ Tbilisi’s surroundings by setting aside several large-scale landscapes such as Lisi Lake, Tbilisi Sea, and Mtatsminda mountain to provide ecosystem services.

They prescribed forest plantations to reduce wind speed and improve air quality, limit summer temperatures, and reduce landslide hazards; they set aside swathes of land for the flow of fresh air and rainwater infiltration zones to prevent catastrophic flooding.

Starting in the 1920s-30s, foresters planted pine trees, selected for their ability to grow quickly in poor soil conditions, throughout the city and its periphery.

Planting later accelerated throughout the 1950s-60s, and it is these plantations that are dying from infestations of pests and fungi.

Polish fashion models on Mtatsminda Mountain. Photo: iconic Georgian photographer Guram Tikanadze (1932 – 1963) from Literature Museum Collection, Georgia, Tbilisi.

In addition to the pine forests, these essential landscape infrastructures are in poor condition due to lack of maintenance, investment, climate change and urban encroachment.

But there is no tragedy here”, Koberidze explains. “At the time, the decision to go ahead with pine trees was correct. They have a life expectancy of up to 120 years, but given the harsh conditions, this 60-70 year life-span we are seeing is not unexpected.

Throughout the years, these trees have stimulated the growth of a humus – a solid, nutrient-rich layer of topsoil, thanks to which we will be able to plant other trees that will make the landscape more interesting and be more durable in the local environment.”

Planning and building the forest of the future

Work to protect and bolster the resilience of Mtatsminda is backed by 16 million GEL (nearly 5 million USD) in funding. This large-scale investment in the forest will ensure the survival and enhancement of this vital natural resource for future generations.

A resource for both humans and wildlife, Mtatsminda has great biodiversity due to its steep slopes, meadows, plateaus and wooded ravines. The Tbilisi Urban Forest project will join the work of scientists and designers together to grow a truly Georgian landscape over what will span nearly 700 hectares.

Experts have gathered data for over a year, using both remote sensing and field data to generate a master plan. Photo: Nino Alavidze/Agenda.ge.

Experts have gathered data for over a year, using both remote sensing and field data to generate a master plan. Photo: Nino Alavidze/Agenda.ge.

The team includes geographer Giorgi Gotsiridze of Geographic, biologist Irina Danelia, botanists Nikoloz Lachashvili, zoologist Niko Kerdikoshvili, environmental scientist Gia Sofadze and economist Etuna Munjishvili.The team analyzed this data to identify areas of critical concern, such as landslide-prone slopes and wildlife zones requiring protection and reduced human impact, and defined the boundaries of the project to limit further urban encroachment.

New trails and infrastructure

In addition to the reforestation project, workers are rehabilitating Mtatsminda’s mult-iuse trail system. Improvements include rubbish removal from trailheads, new wayfinding and signage, overlooks and rest spots, erosion mitigation, and separate trail systems for hiking and mountain biking. A new environmental center will be built near Tsavkisi that will include interpretive exhibitions about the urban forest.

Thousands of seedlings

This summer, the project is in full swing. At Kakheti’s Karibche, a tree nursery in Sartichala, director Vakho Tsulikidze and his team are propagating the thousands of seedlings required to reforest the mountain. On the slopes of Okrokana, workers are digging holes to prepare for fall planting and installing irrigation to support the seedlings through the dry summers. The planting project for the entire mountain will take at least four years.

Karibche nursery in Sartichala. Photo: Karibche nursery.

Urban forestry specialists at Ruderal, a landscape architecture and planning studio in Tbilisi, collaborated with local experts to develop species mixes to replace the monocultural plantings of the past. Mtatsminda features a wide range of exposures, moisture levels, and soils, so each “forest patch” is adapted to a specific ecological niche.

In Tbilisi, most public spaces are planted with a generic palette of trees and shrubs imported from abroad. Our hope is the new plantings on Mtatsminda will bring attention to the form, beauty, and function of Georgia’s endemic tree and shrub species. Ultimately, we hope this work will increase demand for the use and propagation of local species for civic and commercial projects”, said Sarah Cowles, director of Ruderal.

The patches include low-growing shrubs and taller trees to provide cover for birds and wildlife and provide visual interest. Unlike the pine and cedar monoculture planted in the late 20th century, the new patches create varied conditions and experience. They include texture-rich open shrubland (the ‘Savanna Edge’ patch) to silver-canopied mountain woodland (the ‘Celtis Forest’ patch) to the immersive, colorful, bountiful forest (the ‘Fruit Grove’ patch). Each of the patches is distributed across the mountain in massive drifts.

“Planting in large groups, rather than scattered fragments, increases the ecological potency and regenerative potential of each patch type,” said Christian Moore, landscape architect at Ruderal. “The large drifts will also have a significant aesthetic impact, both from within the forest and from far away, especially when the trees will bloom and the leaves change color.”

Scripting for diversity and adaptation

The scale and complexity of the urban forest project required innovation in design technology. Ruderal’s designers developed a custom planting design tool in Grasshopper, a digital modelling software, that allows designers to integrate broad-scale GIS with field-sourced data such as soil depth and composition. Dubbed ‘Okrokana’, the tool produces rapid visualisation of the patches at different scales, optimises plant quantities, and allows designers to simulate the interaction of diverse species over time.

At the Ruderal studio, physical models reveal the spatial and atmospheric impacts of proposed planting schemes. Here, paper trees and pins capture the different plant communities that will be used to revegetate the Narikala Ridge.

“Our practice is engineered to address these exciting urban landscape rehabilitation projects, and we can apply the methods and technologies we applied to Mtatsminda to afforestation projects throughout Georgia”, says Ruderal’s Cowles, noting the same model could be implemented throughout Tbilisi’s large-scale open spaces like the Tbilisi Sea, Khudadovi forest, and the Lisi Plateau.

Encouraging public participation

The Mtatsminda Urban Forest aims to exemplify a new direction of environmental imagination in Georgia.

Public works of this scale are meaningful to young people, including those who moved abroad for work or education, like Natia Kapandaze of Gori, who is now a landscape architect in Austin, Texas.

“I decided to study landscape architecture in the US, where a professional landscape architecture education includes the study of large-scale urban landscapes. The Mtatsminda project is a huge step forward for our community to address climate change and the quality of life in Tbilisi. We have already experienced the consequences of several ecological and environmental mistakes. I believe this project will be the turning point and become a model for future projects”, said Kapanadze.

The Development and Environment Foundation’s Koberidze agrees, who hopes the project will enable thousands to ‘leave their mark’ on the mountain for centuries to come and develop a stake in the city’s greener future. Photo: Nino Alavidze/Agenda.ge

“We’re keeping a list of everyone involved. We have tried to include students in forestry, biology and other faculties in the project in order for them to learn something. Right now, we’re busy digging holes [for the trees] on the south slope between Okrokana and Mtatsminda, and 90% of those involved are from Okrokana itself, and they tell us that their grandparents were involved in the creation of the first forest. It’s so gratifying to see the joy they feel that their own grandchildren will be proud of them for giving new life to the city.”

Tweet

Tweet  Share

Share